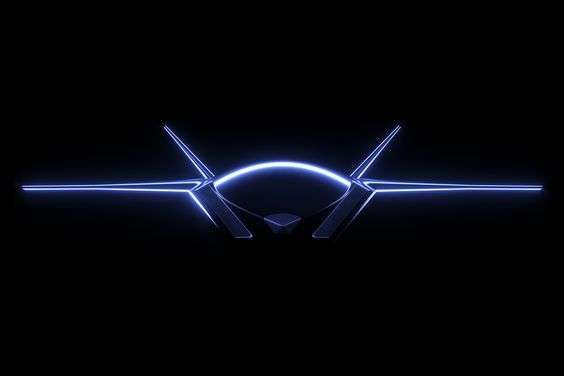

Human-piloted warplanes with drone wingmen are the air combat of the future.

The Air Force believes that drone wingmen working alongside human-piloted jets will be the future of air combat.

But how will the human pilots inside F-35s or the Next Generation Air Dominance platform interact with and direct collaborative combat aircraft? Will these drone wingmen be ready to battle in a future conflict under the orders of their human pilots?

Heather Penney, a former F-16 pilot and senior resident fellow at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, argued in a paper that the Air Force must do more to establish the framework for human-machine interaction.

And if those steps are not accomplished promptly, drone wingmen may not be completely trusted by the pilots flying beside them, and the notion of manned-unmanned teaming may be less effective than it could be.

Penney said in her study “Five Imperatives for Developing Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Teaming Operations” that “teaming must be integrated into from the outset.” “The success of CCA in warfare will be determined mostly by how well they collaborate with humans, rather than capabilities such as the guns and sensors they carry.”

This includes ensuring that the human pilots can undertake the responsibilities necessary to lead the autonomous or semi-autonomous wingmen without becoming overwhelmed, according to her.

Operators must also be included in the process of producing drone wingmen from the start, and given the tools, they need to understand how they should function in combat, according to Penney.

Pilots must be able to rely on the drones and believe that their autonomous capabilities will perform as intended, as well as maintain control over them even amid quickly moving, chaotic engagements, according to Penney. And teams of human pilots and drone wingmen must be customized to each other’s skills, she wrote.

Recommended to read: Meet the SR-91 Aurora: A Mach 5 spy plane that might change everything

saber rattling

Excellent potential

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has stated that developing a fleet of drone wingmen in conjunction with the F-35 and Next Generation Air Dominance platform is a major priority and that competition to develop them is expected to take place in 2024.

Penney stated in her study that the CCA concept “has significant promise” and may potentially provide the Air Force with a decisive battle edge in a fight with a foe such as China.

If the Air Force deploys them in sufficient numbers to make a difference, she believes they will improve the service’s combat capability, create a force mix that can better weather battle losses, and provide theatre commanders with a reserve of aircraft that can be used to surge operations.

Penney wrote that they could also give the Air Force the ability to stage more complex operations that could overwhelm an enemy’s defenses. These drones could be outfitted with a variety of sensors, weapons, and other equipment to conduct airstrikes, jam enemy signals, conduct reconnaissance, or serve as decoys to distract enemy forces or lure out their air defenses.

While the drones will require a combination of traditional software and machine-learning algorithms to guide their autonomous capabilities, she wrote that they will still require human guidance.

To the drawing board

As a result, Penney believes it is critical that the Air Force focus on “human factors engineering,” or how humans interact with the technology with which they operate.

This entails engaging warfighters into the process of designing CCAs as soon as feasible, as well as collaborating with software developers to determine how they will function in battle, she explained.

If that doesn’t happen — and so far, according to Penney, it hasn’t — the Air Force risks building a CCA design that isn’t as successful in war as it could be.

“Collaborative combat aircraft are designed to work alongside human warfighters, yet for the most part, warfighters are excluded from CCA development,” Penney said.

“Collaborative combat aircraft are designed to work alongside human warfighters, yet for the most part, warfighters are excluded from CCA development,” Penney said.

The Air Force can’t wait until drone wingmen are deployed to figure out how they’ll act since the dynamics of how they’ll interact with people must be included into their programming, algorithm development, and training procedures.

It’s also unclear how pilots will control their drone wingmen, according to Penney. According to her, the industry is now trending toward voice directions rather than distracting the pilot’s concentration by typing instructions on a tablet or display.

Voice control has its own set of issues, she says, such as how to operate several drones, how well it would function in warfare situations, and whether the system would properly grasp what the operator was trying to say.

“Does Siri still don’t understand me?” Penney said. She believes CCAs will require various control techniques for robustness, so the pilot may switch to a different control system if necessary.

Human contact

Penney told reporters that having a second operator, aside from the pilot of a manned fighter, controlling or sharing control of that jet’s drone wingman is not something she supports since it might lead to confusion and contradicting orders.

“It’s critical that you don’t split leadership of that formation,” Penney said to reporters.

Autonomous or semi-autonomous drones might potentially operate “untethered” from a specific manned aircraft, either as part of a swarm or as part of an electronic warfare network directed by an air battle manager. She suggested that the air battle managers in charge of the untethered CCAs may operate from a nearby E-7 Wedgetail or E-8 Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System, or JSTARS.

CCAs will not replace human pilots, according to Penney, since people can improvise and adapt to the job.

“Humans will always have a cognitive edge within the battlespace, in terms of making decisions in the face of ambiguity, depending on intuition, breaching laws and conventions, and being able to deploy adaptive thinking from previous life experiences in new and unusual ways,” Penney added. “Autonomy is just not capable of doing that.”